We Have Come so Far, One Wonders, How Far We Can Go?

The Klamath River Watershed is a convoluted landscape shaped by colliding tectonic plates, fire and ice. For Modern Man, it is ripe with political dilemmas, survival needs and ethical nightmares.

Clockwise: Klamath Marsh Refuge, Crooked Creek, Iron Gate Dam, Klamath River Estuary, Sugar Loaf Mtn - Ishi Pishi Falls and rafting on Upper Klamath River.

Anders Tomlinson spent 13 years looking, listening, filming and recording in the Klamath River Watershed. He had several watershed moments including the day he read in the newspaper that Sacramento River interests were fighting Trinity River interests over water to protect environmentally endangered salmon in both the Sacramento and Trinity Rivers. Both sides had federal lawyers facing off against each other in court. What does one do? What do we do? Â

It Is Helpful To Know Where We Came From to Understand Where We Are..

The first European miners-settlers, traveling from the mouth up the Klamath River enroute to build a mining settlement, which is now Happy Camp, thought the Trinity River was the main-stem and the Klamath River was a tributary. The underwater canyon that is carved in the ocean bottom off Klamath California was named Trinity Canyon not Klamath Canyon. The miners promptly set the forests on fire. Â It was the easiest way to reach bare ground in a land of steep canyon walls. Â When the winds were right the smoke choked Portland. Â Nautical maps made note of smoke off the coast as a navigational hazard. That was then.

Today, there is a need to rethink our ideology on a host of issues including those considered politically correct or untouchable. Here is an opportunity to refocus man’s relationship in, not to, nature. Food, water and shelter are in jeopardy for all stake-holders and species. Welcome to the age of Anthropocene. Welcome to the Klamath River Watershed. This is now. For geographical and historic background visit Klamath River Watershed in pictures and words.

Watersheds are for flora and fauna. Watersheds change over time.

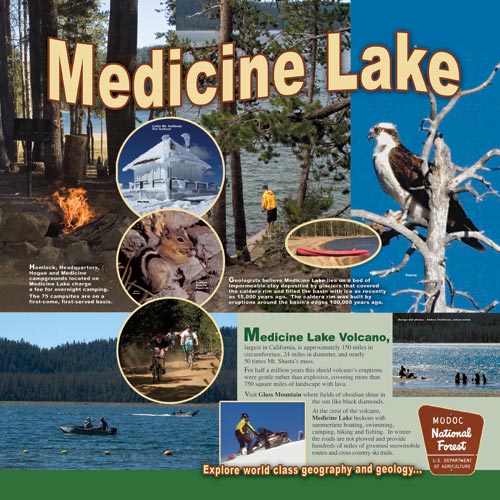

The Klamath River Watershed, see video, is clearly defined. Waters flow downhill to creeks, streams and rivers that flow to the Klamath and Trinity rivers, which join some 40 miles from the Pacific Ocean, and empties into the sea. This is exact – no room for interpretation.  It is a place with absolute boundaries. Water flows this way or that way.  The Klamath Basin is a headline that means different things at different times to different folks. As example: in a judge’s decision that returned water management to the flows required by Hardy phase 2 she described the Klamath Basin as being the land that makes up the Klamath Reclamation Project and later on in the decision as being all the lands that are coho habitat.  Two different worlds.  If a judge is confused about where is where what can we expect from the general public or public servants?

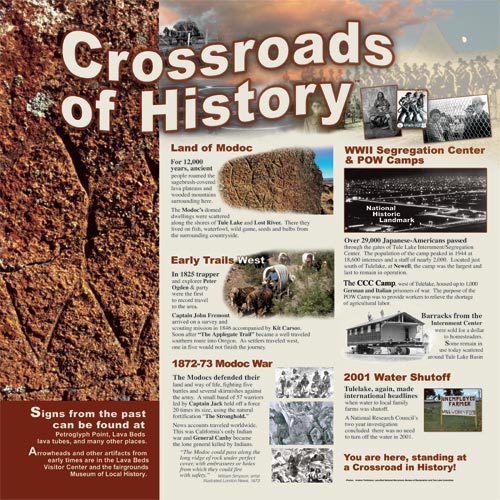

In 2001, several young farmers interviewed by national media kept trying to say the salmon issue was about a much larger watershed – not just the twenty some miles that makes up the Klamath Reclamation Project. The media would not listen. European media did listen and reported as such.  The National Academy of Science, 12 good scientists from around the country who spent three years studying the 2001 salmon-water shutoff, determined it was not a Klamath Basin problem – it was a Klamath River Watershed problem.  Few listened.

In the Klamath River Watershed there is little flat space. Where there is flat space with water running through it there are people, and there are few people living in the Klamath River watershed. The largest population is concentrated around Upper Klamath Lake in the Upper Klamath Basin where the Klamath River begins its 263 mile journey.

We Huddle in the Future’s Shade Waiting for Light.

The Klamath Water Users Association presented a series of tours from 2001 through 2008 to introduce Klamath River Watershed stake-holders to the Klamath Reclamation Project. Anders documented two National Academy of Science panel tours, along with Pacific Ocean fishermen, News media, Klamath Indian Tribe and Upper Klamath Basin resident tours. All present had much in common. They are humans capable of doing “good” things and “bad” things in pursuit of their needs and expectations.

The Centennial Celebration ended Anders’ shooting in the Klamath River Watershed.

Things had changed. The 114th Federal study of Upper Klamath Lake determined cattle should be kept away from streams and springs. Anders photographed in July 1995 cows wading across the Wood River that empties into Upper Klamath Lake. Access is now fenced off. Much has changed and much has stayed the same, it is the way humans do human things.

There are behaviors, relationships and synergies to celebrate. There are voices and concepts to listen to and consider. Polarization, ethnicity, projections, anticipations and fear of change shout louder, and have a larger audience, than seeking, understanding, embracing and compromise. It is here that these films of the Klamath River Watershed begin.

These are stories of human nature reconciling itself with human nature.

©2011 Anders Tomlinson