Life on the Refuge

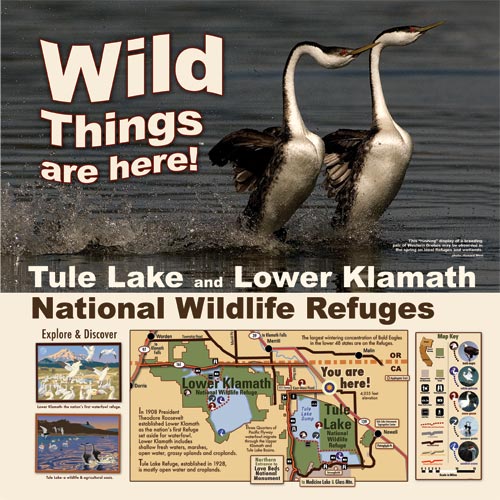

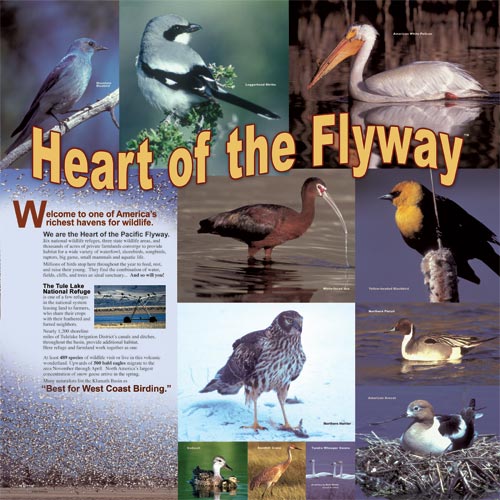

The Klamath Basin National Wildlife Complex includes six diverse refuges that encompass over 200,000 acres. They straddle the California – Oregon border. Here, seven habitats offer food and sanctuary to over 450 species. This is an important stop along the Pacific Flyway.

Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, founded in 1908, was the nation’s first waterfowl refuge.

It was followed by five others: Tule Lake, Clear Lake, Upper Klamath, Klamath Marsh and

Bear Valley. Each serves a purpose. Connected, they are a complex refuge of services and needs.

There are summer days with bodies of water, large and small, shallow and deep, moving and still. Waterfowl, many of each, eat and rest, floating or standing. There are windy winter days when wildlife huddle in a frozen world, food is scarce and eagles eat the weak. In spring, man plants his crops and skies fill with north bound waterfowl. For many this is their last chance for food before reaching their arctic breeding grounds. Fall offers refuge to all heading south as man’s harvest comes to an end. This is home to resident mammals, fish, amphibians and birds seasonally migrating across the refuges.

This is life on the refuges. Nature does what it does and everything else adapts or disappears. It is what it is. Mountains surround a vast parade of shifting life. And there are storms. And there are moments of absolute tranquility. This is what my cameras have captured. This is what I have seen and heard. This is what I want to share with the world, a micro-cosmos of life on planet earth.

Walking Wetlands

Land for farming and wildlife refuge continue to be reduced by urbanization. “Walking Wetlands” on Tule Lake and Lower Klamath National Refuges documents a successful program that incorporates the two on a rotational basis. Farm land and refuge become one, a timely recipe for success. The concept is simple. Take farm fields out of production. Build containment and connecting water structures. Flood the fields. Let them grow, managing and mimicking nature’s way, into marshes Do so for three years. Drain and allow entry and exit for farmers and their equipment. Farmers remove the overgrown tules, not an easy chore, turn the soil and plant crops. There is no need to add fertilizers or weed killers, flooding did that work. Magnificent crops grow in reclaimed marshes. Farm until the soil loses it’s nutrients and pesticides are needed. Repeat the process. Flood, water manage and return to agriculture. At all times, wildlife find values in both the marshes and farm fields. Yes, it is a simple process. And yes, it is a complex interaction of various species and ways of life. And yes, it works.

Reflecting

We have so much to learn from nature. My greatest insights have come from field observations. These diverse refuges have taken me to many places in many times. Each of the refuges has a dominant feature that no other has. And each of the refuges share common features. Time is measured in seasons and epochs. These refuges are sustainable existence. Here, the little picture is the big picture. I have had the privilege of knowing these refuges for years after year after year. My greatest moments have been those where I blended into the landscape and became a simple component in a grand movement. A Year in the Life on the Refuges from tule-lake.com.

©2010 Anders Tomlinson, all rights reserved.